In the midst of the Great Depression, while men stood in line for bread and went months without any sort of income, the city of Chicago offered a glimpse into the future. A Century of Progress World’s Exposition was hosted from 1933 to 1934 and focused on the ways the city and country had grown since Chicago’s founding in 1833. The fair “emphasized technology and progress, a utopia, or perfect world, founded on democracy and manufacturing.” And what would a perfect world be without a casino?

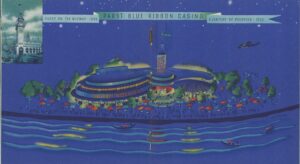

Although Frederick Pabst, who initially made his stand in Chicago history at the Columbian Exposition in 1893, had died in 1904, the Pabst Brewing Company continued to make itself known in the Windy City. For the Century of Progress Fair, a Pabst Blue Ribbon Casino was set up on Northerly Island, a short walk or bus ride from the main campus of the event. It was the largest restaurant available on the fairgrounds, seating for 1,000 diners and featuring an open-air garden able to hold 2,500 patrons.

Pabst Trade Pavilion at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair Columbian Exposition

Though at a large event like the Century of Progress fair it can be difficult to outshine the myriad of other attractions, the Pabst Casino was able to make a name for itself through the music and entertainment offered. A revolving platform was built for bands to make their way around the entire building, offering all visitors a chance to see and hear the music up close. A pamphlet advertising the establishment boasts “this gay, colorful spot will be the rendezvous of famous stage, screen, and radio starts.” Band headliners included Ben Bernie, Guy Lombardo, Buddy Rogers, and Tom Gerun, as well as four orchestras who played music from noon until closing to let guests dance their woes away. The aforementioned Ben Bernie even broadcasted his radio show directly from the casino every Tuesday night.

Pabst Blue Ribbon Casino rendering from a Pabst 1933 World’s Fair booklet

Of course, a restaurant named after Pabst would be nothing without actual Pabst products. Fear not, the pamphlet assures readers that “the nation’s favorite quality beer, Pabst Blue Ribbon, as well as other Pabst beverages and Pabst-ett, is served.” There was also a full bar located in the gardens, encouraging visitors to “make the Pabst Blue Ribbon Casino your headquarters at the fair!”

Pabst-ett Box

Unfortunately, not all was picture-perfect in this supposedly ideal utopia the fair was celebrating. Racial tensions during this time were high, and the fair featured many racist depictions of Black people such as an “Old Plantation Show” and “Show Boat.” The irony of a fair meant to celebrate the new inventions and how far the country has come continuing to stick to its racist ideal is obvious, and many people of color found themselves “[meeting] all kinds of evasions to discourage their patronage, despite the prior assurances that no racial discrimination would be allowed.” The Past Blue Ribbon Casino is no exception, as many Black people reported being ignored by waiters and sometimes kicked out outright.

Although the Pabst Blue Ribbon Casino, like most of the buildings at the fair, is no longer standing, the legacy of the World’s Fair lives on in Chicago. It’s so important, in fact, that a star was added to the city flag to commemorate the event, putting it on the same pedestal as such historical events as the Columbian Exposition, the Chicago Fire, and Fort Dearborn, all of which are extremely significant in Chicago history, emphasizing the importance of not only the exposition itself, but also of all those involved, including the Pabst Brewing Company.

By Nora McCaughey