Wisconsin is known for beer and cheese – but what happens when one of these products is no longer allowed to be sold?

Wisconsinites adjusted, and so did the Pabst Brewing Company. With the introduction of Prohibition in 1920, brewers across the country were faced with difficult decisions as the manufacturing and distribution of alcohol was made illegal. Unlike other brewing companies, though, the Pabst Brewing Company had thought ahead. Even before the official start of Prohibition, as early as 1917 Pabst was producing an alcoholic alternative called Pablo —The Happy Hoppy Drink, which was marketed as a drink that “makes you feel good — and it is good.” This was just water, malt syrup and the company’s old Victorian standby tonic, Pabst Malt Extract.

So when the time came for the ratification of the 18th amendment, the Pabst Brewing Company was ready to shift gears. The brewing company became the Pabst Corporation, which was designed to essentially act as a placeholder, keeping the Pabst business up and running selling non-alcoholic products until Prohibition ended. But Pablo alone wouldn’t do the job.

The idea of making cheese under the Pabst name came from the excess of milk the company had due to the dairy farms owned by the Pabsts. They’d initially acquired farmland in the late 1800s to raise French Percheron horses to pull their beer wagons, but as cars gained popularity and Fred Pabst, Jr. worked to create his model farm in Oconomowoc, they changed to breeding Holstein dairy cows. From there, producing dairy products such as cheese seemed like a natural progression until the sale of alcohol became legal again. The Pabst Company began producing Swiss cheese, but processed cheese was on the rise due to rations during World War I, and chemist Dr. Alfred Schedler of the Pabst Brewing Company was on a mission to create a cheese product that contained more nutritional value than regular cheese.

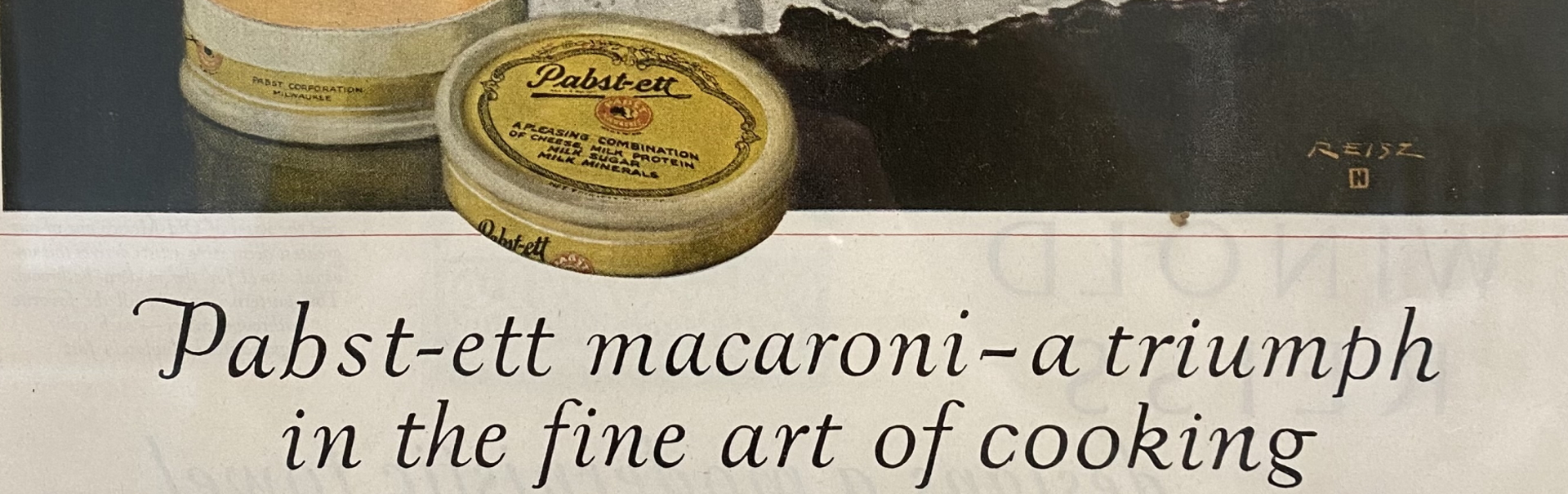

Pabst-ett advertisement from 1927

Thus, Pabst-ett was born, a processed cheese spread that was marketed as “not cheese, but more than cheese.” And unlike beer, Pabst-ett could be marketed toward family members of all ages. One advertisement read “It is as digestible as milk; more nourishing than milk; the cheese-product young children, elderly persons, even invalids may enjoy.” The product was fairly successful, as the company focused on the pure process by which the cheese was created, and even created a housewives’ cookbook based on how easy and versatile Pabst-ett was.

Unfortunately, the marketing tactics caught the eye of the Kraft Cheese Company as well as potential consumers. Kraft had recently started to form a monopoly on the dairy industry by purchasing nearly every cheese company in competition, including Velveeta. Velveeta was known for its spreadable processed cheese, which Kraft saw as the original version of Pabst-ett.

Kraft sued Pabst, forcing them to pay a royalty of one-eighth of a cent per pound in royalties. In 1933, when Prohibition was finally finished, Pabst sold the cheese to Kraft, and Pabst went back to doing what it does best: Beer.

Another variety of Pabst cheese – pimento

From this story one may assume that Pabst-ett was the saving grace for the company during the 1920s, but this may not be entirely true. Frederick Pabst had bought enough property in hopes of building beer gardens, restaurants, taverns, and hotels that much of the company’s money was coming through real estate rather than the production of alcohol. By 1910, the Pabsts owned more than 400 plots in 187 cities, and expanded the real estate business at the same time they produced Pabst-ett. They even leased the brewery space to Harley-Davidson since the building wouldn’t be used until 1933.

The Pabst Brewing Company wasn’t the only alcohol-selling company forced to adapt during Prohibition. Nearly every beer company in the country created a Pablo-like non-alcoholic beverage in an effort to sell products: Schlitz made Famo, Stroh had Lux-o, and so on. Even more creative liberties were taken as some breweries marketed beers meant for medical consumption. Beer historian Maureen Ogle even mentions that “Pabst studied the possibility of investing in artichoke juice.”

A wooden box for Pabst American cheese

Non-alcoholic beverages weren’t the only ways companies found to stay afloat, as the “near beer” idea quickly fizzled out as Americans demanded real alcohol. Coors started to use clay deposits near its manufacturing building to sell ceramics from the Coors Porcelain Company. Busch invested in groceries and common foods like eggs and formula, while ice cream was even produced by companies like Yuengling and Stroh (Stroh’s Ice Cream is still in business today).

So, in the grand scheme of things, Pabst-ett was not the most unique or even most well-planned of the brewery companies’ alternate products. Bad luck (from Kraft) and good luck (from real estate) has led Pabst-ett to go down in history as one of the more oddly infamous cheeses in Wisconsin.

By Nora McCaughey